Tuesday, April 22, 2014

Thursday, April 17, 2014

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Albions Seed-

4 folkways, - a really good framework for beginning to think about USA culture.

Seems to suggest that the extreme individualism of the USA actually comes from conceiving 'liberty' in terms of slave society. Hence any sort of curtailment is almost a form of rule over another reminiscent of slavery.

After a week in Texas I can say the frontier has pretty much remained unchanged.

Notes

Notes

- albions seed

- Germ theory

- frontier thesis

- migration model

- 1629 -1640 puritans to MASSACHUSETTS (E. ANGLIA)– “ordered liberty”

- public liberty w constraints on individual – freedom to be in community

- specific liberties from prior constraint

- soul liberty – religious freedom

- collective obligation – freedom from want/fear/circumstance fundamentally

- 1642 – 1675 royalist elite and indentured servants to virginia – ANGLICAN hegemonic liberty

- liberty as dominion over others (slaves) and over ones self

- power to rule vs subject to ruled over (slavery)

- 1675 – 1725 english midlands and wales to DELAWARE

- Quakers

- universal liberty , extended to all esp. religious freedom of conscience. cf religious persecution

- rights of englishmen: right and title to own life, liberty and estate; representative government; trial by jury

- became antislavery after first decade

- 1718-1775 nth britain and nth ireland to appalachia backcountry- border idea of natural liberty

- against constraint and anti law and order

- natural freedom – want the wild

- not transgressors

- european folk culture (british border country of anarchic violence – already libertarian) with american environment

- patrick henry – minimal govt, light taxes, armed resistance

- border culture

- william cotesworth

- doesn’t tolerate dissent or deviance; opposition met with force

- opponent = enemy; intolerant

- “elbow room”

Friendly Societies 1

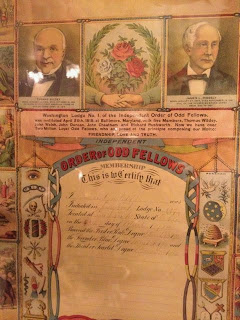

I recently got back from Texas where I visited an antique shop in which I found these interesting banners belonging to the International Order of Odd Fellows. The IOOF are a "friendly society" which originated in Britain in the 17th C and was later brought to the US and then to many countries in the world. The three pillars that they follow are love, truth and friendship. I think I'd like to make some similar banners, but am still anticipating connexions B and C. I suspect it would be in the form of investigating the visual culture of the rural friendly societies in the developing world, and tracing connections to those in the West.

The French Revolution caused "the establishment" to view organisations such as the Oddfellows and Freemasons with fear. Membership became a criminal offence in France, and such organisations were driven underground and forced to use codes, passwords, special handshakes and similar mechanisms. Fear of revolution was not the sole reason for persecution; Friendly Societies like the Oddfellows were the predecessors of modern-day trade unions and could facilitate effective local strike action by levying all of their members for additional contributions for their benevolent funds, out of which payments could be made to the families of members who were on strike.

In 1911, when Asquith's Liberal government was setting up the National Insurance Act in Britain, the Oddfellows protected so many people that the government used the Oddfellows' actuarial tables to work out the level of contribution and payment required. At that time the Oddfellows was the largest friendly society in the world. Since the welfare state of 1948, the role of the Oddfellows has been to move into financial products.

The IOOF was brought to the US by ex-pat Thomas Wildey in 1819, and they later separated from the English branch. After the Civil War, with the beginning of industrialisation, the deteriorating social circumstances brought large numbers of people to the IOOF and by 1889, the IOOF had lodges in every American state. From 1860 to 1910/1920, also known as the "Golden Age of Fraternalism" in America, the Odd Fellows became the largest among all fraternal organisations, (at the time, even larger than Freemasonry). By 1915 the IOOF had 3.4 million active members worldwide. The IOOF declined in membership in the US with the New Deal, and generally everywhere with the welfare state.

Interestingly, some new chapters have sprung up in even the last 20 years such as in Estonia and Dominican Republic, and Italy in 2010. On the other hand orders have existed in Nigeria since the 1800s which were re-established in the country in 2008.

Many of these societies still exist in the developing world often as rural banks or ROSCAS (Rotating Savings and Credit Association). These tie payments to seasonal cash flow cycles in rural communities and are said to aid savings where family and relatives may demand access to savings, where there are low levels of literacy and where there are weak systems for protecting collective property rights.

Interestingly, some new chapters have sprung up in even the last 20 years such as in Estonia and Dominican Republic, and Italy in 2010. On the other hand orders have existed in Nigeria since the 1800s which were re-established in the country in 2008.

Many of these societies still exist in the developing world often as rural banks or ROSCAS (Rotating Savings and Credit Association). These tie payments to seasonal cash flow cycles in rural communities and are said to aid savings where family and relatives may demand access to savings, where there are low levels of literacy and where there are weak systems for protecting collective property rights.

They take various cultural forms, according to wiki:

Variously called "committee" in India and Pakistan, Ekub in Ethiopia, Susus in Southern Africa and the Caribbean, "Seettuva" in Sri Lanka, tontines in West Africa, wichin gye in Korea, arisan in Indonesia, likelembas in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, xitique in Mozambique and djanggis in Cameroon, ROSCAs are informal or 'pre-co-operative' microfinance groups that have been documented around the developing world. A famous early study by anthropologist Clifford Geertz documented the arisans of Modjokuto in Eastern Java. He described them as "an "intermediate" institution growing up within peasant social structure, to harmonize agrarian economic patterns with commercial ones, to act as a bridge between peasant and trader attitudes toward money and its uses."The individuals in the ROSCA select each other, which ensures that participation is based on trust and social forces (see Social capital), and a genuine commitment to participate.

Tuesday, April 8, 2014

From Graeber's 'Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology'

Residents of the squatter community of Christiana, Denmark, for example, have a Christmastide ritual where they dress in Santa suits, take toys from department stores and distribute them to children on the street, partly just so everyone can relish the images of the cops beating down Santa and snatching the toys back.

Monday, April 7, 2014

McGowan II

"Enjoyment has an inverse relationship to utility: we enjoy in proportion to the uselessness of our actions. "

Sunday, April 6, 2014

Wes anderson III

So i think one defining thing about culture really is how it constructs childhood. And one of the funniest parts about continental europeans (from my cultural pov) is that they dont have an infantilising culture.

On one hand, USA is all about feeding adults kids food and hollywood endings so that they never have to grow up, while australia and england are all about teenage culture so men can have boys clubs (hang with the lads, gentlemans clubs, go out in groups) so they can avoid the the anxiety of male-female sexuality. On the other hand, Continental 5th graders are already expected to have formed their own opinion on Wagner and/or Hegel, personal interests (collecting spoons from 1789, 1848 and 1917), ...

I think when you once said that Tennenbaums is about Americans imagining Europeaness, it is particularly in relation to this issue of childhood. In all of Wes films he breaks down this distinction between childish adults and adultish children, as an embodiment of the crisis in the patriarchal order, breakdown of the 1950s nuclear family. I wonder if somehow this can be mapped onto a Trans-Atlantic cultural relation?

_________________

Thursday, April 3, 2014

Conspiracy Theories

This still doesn't explain if or why conspiracy theories are a predominately American art form.

From Todd McGowan:

Confronting the inconsistency of social authority is not an easy task

for the subject. Many try to sustain a belief in its consistency through an

imaginary construction that represses contradictory ideas. The problem

with this solution is that these ideas become more powerful through their

repression, and the result is some form o f neurosis. Another possibility

is the paranoid reaction. Rather than trying to wrestle with the problem

of the gap in authority, the paranoid subject eliminates it by positing an

other existing in this gap, an other behind the scenes pulling the strings.

As Slavoj Zizek explains it, “Paranoia is at its most elementary a belief into

an ‘Other of the Other,’ into an Other who, hidden behind the Other of

the explicit social texture, programs what appears to us as the unforeseen

effects of social life and thus guarantees its consistency: beneath the chaos

of market, the degradation of morals, and so on, there is the purposeful

strategy of the Jewish plot.”36 The comfort that paranoia provides for the

subject derives solely from this guarantee. For the paranoid subject, the

surface inconsistency of social authority hides an underlying consistency

authorized by a real authority whom most subjects never notice. Paranoia

simultaneously allows the subject to sense its own superiority in recogniz

ing the conspiracy and to avoid confronting the horror of an inconsistent

social authority.

...

But Stone is not the only leftist to turn to paranoia. Many do so in order

to confront forces that they otherwise couldn’t identify. Among those who

suffer from political oppression, paranoia and conspiracy theory serve as

vehicles for thinking through systems of control and even mobilizing action

against those systems. As Peter Knight points out, “Conspiracy thinking has

played an important role in constituting various forms of African American

political and cultural activism.”38 When it directly produces activism, the

political valence of paranoia seems to tilt more clearly to the left than it

does in the case of Stone’s film.39

Marxist Fredric Jameson focuses on a related aspect analyzes the paranoid film in The Geopolitical Aesthetic. In this work, Jam eson aligns conspiracy theory with what he calls cognitive mapping — the attempt to think the global capitalist system in its totality. The diffuseness of global capitalism prevents the kind of cognitive mapping that was possible in earlier epochs. Today, in order to think the totality at all, subjects must resort to the idea of a conspiracy. As Jameson points out in his analysis of

All the President’s Men, “The map of conspiracy itse lf... suggests the pos

sibility of cognitive mapping as a whole and stands as its substitute and

yet its allegory all at once.”40 Jameson’s statement reflects his ambivalence

about conspiracy theory and paranoia — even though it allegorizes cognitive

mapping, it also substitutes for it — but he nonetheless sees its usefulness as a strategy for the Left, especially when facing the global capitalist leviathan.

The problem is that even when it works to mobilize subjects to fight

against an oppressive system, paranoia has the effect of depriving subjects

o f their agency. By eliminating the gap in social authority and filling in this

gap with a real authority who effectively runs the show, paranoia deprives

subjects of the space in which they exist as subjects. The subject occupies

the position of the gap in social authority; it emerges through and because

of internal inconsistency in the social field of meaning. The extent to which

paranoia allows the subject to experience social authority as a consistent field is the extent to which it works against the subject itself. Even if it manages

tangible political victories, emancipatory politics that relies on paranoia

undermines itself by increasing the power of authority in the thinking of

subjects and decreasing their freedom. W hat’s more, it doesn’t actually

work.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)